Do You Realize How Biased You Are?

Has anyone ever accused you of being biased? If so, you probably assumed it was a negative criticism of your behavior or thinking. Every one of us is biased, yet few people realize the extent. The research I have done on this subject clearly shows that people are a lot more biased than they realize they are, but is this a big problem? The more I thought about it, the more interesting the subject became, so I decided to summarize my learning and relevant experience with bias in this post. I hope you find it interesting and maybe helpful in how you conduct your day-to-day decision making.

What Does Being Biased Mean?

The standard dictionary definitions of “biased” say it means you’re prejudiced for or against a person, a group, or thing. The word also implies you’re being unfair. This probably makes you think of those who oppose the fight to end school segregation and other battles for acceptance in society by minorities such as LGBTQ+ and immigrants. Well, that’s a correct use of the word.

But I also found this word has a more important meaning when applied to demanding disciplines in our society, such as the judicial system and scientific research. In these latter examples, the word can define serious omissions and false conclusions. Now we’re getting into potentially very big problems. Let me offer some examples from my own experience, along with some of my opinions.

Bias Can Be a Very Big Problem in Consumer Research

I was introduced to the principles of consumer research in grad school at the University of Illinois. One of the most interesting stories I read about was how George Gallup revolutionized readership research when he did his Ph.D. work at the University of Iowa in 1928. Up until then, newspaper and magazine publishers assumed all they had to do to find out what parts of their content were read, was to simply ask the people who were regular readers. I remember my search in the Illinois school library produced a learned article by a Northwestern University professor who summarized his recommended newspaper readership research process in 1914 as follows:

Mail readership questionnaires to all subscribers of the publication.

Ask the man of the house to check which articles he read and return the form.

Count the number of readers for each article.

In 1914, this sounded almost “scientific”, I think, because you were asking male readers to report what they read. Then you used math to determine the level of readership for each article. What could be wrong with this method? A lot, it turns out.

In 1928, George Gallup said men often lied about what they read, when asked, to maintain a desired image at the time. What the 1914 method showed was that men always read the headlines, the stories about government policy, and almost never read the comics. Gallup proposed a much different method of doing readership research. He had an interviewer present the publication to the respondent, then point to each article, one at a time, page by page, asking each time, did you read any of this, some, or all of this? The results were shockingly different. Male respondents now reported that they hardly read government policy articles, and always read the comics—a complete reversal of frequency for these types of content reported in the 1914 method. The learning was simple. People can only be trusted so far, when reporting on behavior that has ego-building implications in society at large.

What was biased about the 1914 research method? The question asking was biased; men at the time, could not be trusted to report what they read honestly.

George Gallup later got involved in another kind of research bias problem that has become famous among researchers. In 1936, the Literary Digest magazine conducted a poll among its readers in an effort to predict the winner of the presidential contest that year between Republican Governor, Alfred Landon of Kansas, and incumbent, Democrat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Over 2 million votes were counted, and the magazine announced a “Landslide for Landon”. But they were dead wrong. Roosevelt got over 57% of the actual popular vote.

What was biased about the Literary Digest poll? As Gallup explained afterward, the sampling was biased. The magazine was read by upscale, somewhat intellectual subscribers. They did not parallel the total U.S. voter population. The misleading assumption was that many voters can’t be wrong. The size of the sample has been shown to be not as important as its representativeness of the sample to the entire voting population. Even a sample size of 2 million, if biased, will incorrectly predict the actual election outcome.

What Other Forms of Bias Are Problems in Research?

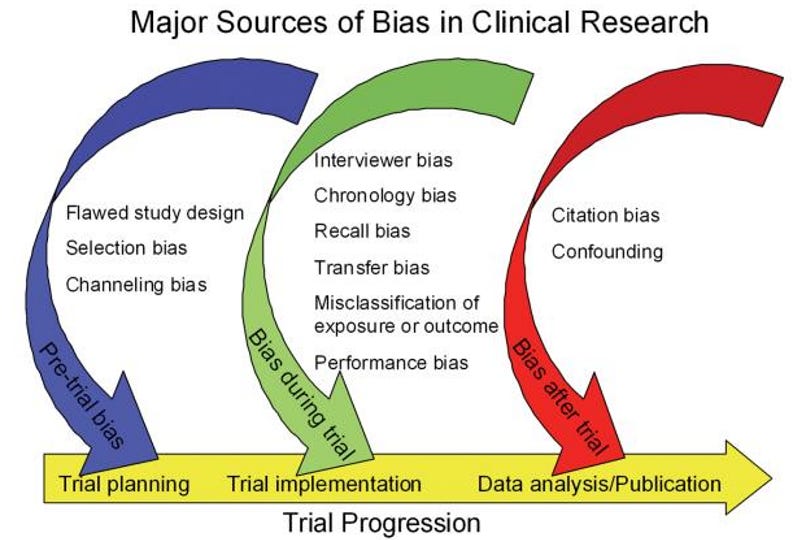

This list of possible research biases is too long to even list in this post. If we try to summarize these types of biases it can be done by the three standard phases of a research project; Pre-trial planning, Implementation, and Analysis biases as indicated below:

It is generally agreed among the many branches of scientific testing that the biases most likely to cause the most trouble are those classified as unconscious biases; the automatic assumptions or stereotypes we all have about certain groups of people outside of our conscious awareness that influence our attitudes and behavior concerning them. Unconscious bias, also often referred to as implicit bias, is pervasive and often does not align with our expressed or declared beliefs. Said simply, they cause conflict in our thinking at the subconscious level and, therefore, are not immediately known to us. The influences of other people we interact with can also influence our thinking and assumptions without us being aware of it. Even a casual review of a list of the many cognitive biases that have been identified is simply “breath-taking”.

The Important Problems of Bias in Our Judicial System

For many years, the ultimate evidence in court cases was thought to be “eyewitness testimony” for a crime. In the latter part of the twentieth century, however, this assumption began to change. In 1967, the US Supreme Court acknowledged the dangers of inaccurate eyewitness testimony. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) created a task force in 1998 to address the issue in response to growing research on the unreliability of eyewitness testimony. A major cause was the increasing number of DNA exonerations revealing wrongful convictions. In 2015, the Supreme Court approved and recommended the use of the Model Eyewitness Identification Instruction, explaining that eyewitnesses are often expected to identify perpetrators of crimes based on memory, which is incredibly malleable. Under intense pressure, through suggestive police practices, or over time, an eyewitness is more likely to find it difficult to correctly recall details about what they saw.

John Douglas, the highly praised pioneer of new FBI profiling techniques for the worst serial killers, became an important contributor to jury education. He was frequently called as an expert witness to educate juries on the problems of eyewitness testimony.

The Conflicting Power of Our Own Emotions and Feelings

It is generally agreed that an awareness of our own implicit biases is a critical first step in seeing and developing our own self-awareness. For this reason, it is important to at least indicate the powerful influence our own emotions and feelings have in creating the mental conflicts that often result in eyewitnesses biases.

It should be obvious to you, if you’ve read this far, that we cannot help being biased, because our brain does not record what we see, hear, or otherwise experience through our senses like a lifeless machine. Instead, our living brain is constantly organizing, focusing, and filtering our experience instantly.

Our emotions and feelings always play a critical role in how our experiences are perceived and remembered. It’s important to remember what Dr. Antonio Damasio said about what our brain is programmed to automatically do - that is, to survive and prosper. Remember that your sensory input is from your immediate and local experiences. Basically, your brain wants to be sure that you are in sync with, or compatible with, your surrounding environment, and that includes what people around you are doing and what is physically happening around you. If the people have wrong information they are operating from, your brain wants to know how to be compatible and survive in their presence.

Dr. Damasio, like most brain scientists, distinguishes between emotions and feelings, by saying emotions are deeper, often only subconscious, and our feelings are ways our conscious mind interpretsts and reacts to our deeper emotions. But both emotions and feelings are given the same names, so I will use these common names without trying to further distinguish between emotions and feelings.

Continuing my personal interpretation of what Dr. Damasio as well as other neuroscientists have said about what we want, or are trying to accomplish, I would suggest the following major motivations at work:

We want to survive physically, and in terms of our ego state—however we define that self-identity at the time.

We want to feel accepted by the group we feel we belong to

We want to feel important to those and other people around us.

What we do and think at the moment, is strongly influenced by the specific emotions and feelings we have. Many writers identify these six basic emotions or feelings:

Sadness

Happiness

Fear

Anger

Surprise

Disgust

Dr. Damasio believes that our brain has evolved from the basic biological evolution of our bodies. In his latest book, The Strange Order of Things, he proposes that our emotions evolved as actions taken by our body to survive and prosper, and emotions led to feelings and the complex nervous system we call the mind. He supports his proposals from a biological as well as neurological perspectives. The brain did not develop by itself, and the brain continues to develop and be maintained by its biological support structures. This finding is the main reason he claims that artificial intelligence can never duplicate what our brains now do.

Dan’s Net Take-Away

It’s obvious that we are not mechanical recording machines. What we see and hear and experience in other ways is strongly defined or even re-defined by the ongoing needs and functioning of our brain. Where and when our biased experiences can be a problem is a question each individual must ask, but obviously our biases are potentially dangerous in any type of scientific examination and if we are called to testify as eyewitnesses in a court case. Always be aware of your potential biases.